Welcome to our combined Q4 and 2020 Malware Threat Report. We will look at how the threat landscape changed in Q4 and take a more in-depth look at the malware that dominated 2020.

Our previous malware threat report for Q3 2020 saw a significant rise – nearly 50% – in traditional malware, exploit based threats, and coinminer attacks. However, adware/PUA, mobile, and script-based threats saw a decline compared to the previous quarter. This reduction was reversed in Q4, which saw increases in almost all types of malware.

Threat Summary

In 2020, overall threat detections surged by 47%, and adware nearly doubled over the previous quarter; Office, script and coinminer malware all increased by more than 50%.

None of these threats were new to Q4; they developed through 2020, so what were they?

PE Malware Threats

Portable Executable (or PE) is commonly used to describe binary executables within the Windows OS. It includes .exe, .dll, and .scr file types. These files are widely leveraged in malware attacks because of their small size, have the advantage of being unreadable and of course, they are part of the most commonly used OS. Most importantly, unlike other file types, their malware can be self-contained and not require additional resources (extra files or external links) to effect an attack.

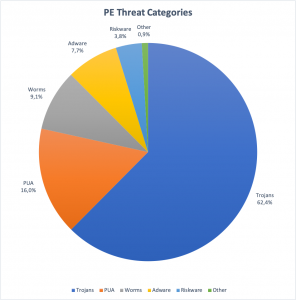

Let’s have a look at the types of PE attacks that were seen in Q4.

In the chart above, we see trojans form nearly 2/3rds of all PE-based attack. PUA and Adware make up 16% and 7%, respectively, with worms representing about 9%. Beyond this, there is a small percentage of riskware and miscellaneous detections.

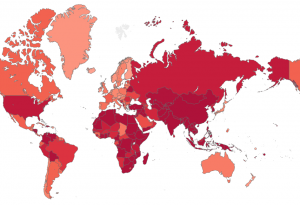

A heat map shows the distribution of attacks on a per user basis. We see a clear focus on Asia and Africa with a lower overall threat level for Europe & Australia. The countries with the greatest number of registered attacks per device include Egypt, Bangladesh and Indonesia. Other countries that are high on this list are Vietnam, South Korea, China and India.

To put things into perspective, in 2020, a user in the USA or Russia (high PE risk) was four times more likely to get attacked than a user in Japan or Germany (medium PE risk). However, someone in Egypt or Indonesia (very high PE risk) was five times more likely than someone in the US to face a non-PE malware attack.

Emotet

Emotet is one of the most disruptive malware of recent times. Email campaigns using Emotet are very periodic, with breaks of complete silence between attacks. Emotet‘s highest activity was seen in December 2019 and February 2020. It then hibernated for nearly half a year. In the second half of the year, we saw campaigns on and off though August, September and October. Since then, we have not seen a new wave of phishing emails.

Emotet is a loader, a trojan designed to get into any system and then deploy threats. Recently it brought us TrickBot, incredibly modular and flexible, and the Banker/Backdoor QBot . It was previously used to deliver Ryuk ransomware.

The initial infection vector is often an email with a fake invoice or delivery notice . This is used to trick the potential victim into opening a file containing the malware. Stolen email addresses and contact information are elements used to trick potential victims into thinking the email comes from someone they know, a procedure known as ‘Dynamite Phishing’.

In early January 2021, law enforcement agencies took down a large part of the Emotet infrastructure – time will tell if we have seen the end of Emotet.

GoLang based Malware

The popularity of GoLang (or simply “GO”) programmed malware increased in 2020. Compiled for any operating system, it allows a developer to write code once and deploy it on any device.

In 2020, malware authors leveraged GoLang’s capability to target Windows, Linux and macOS users with ransomware, info stealers, botnets, and remote administration tool payloads.

One example of a threat abusing the GoLang feature set is Smaug ransomware. Smaug can operate on Windows via PE and on Macs via the MACHO file format.

We first saw Smaug related advertisements around the end of April 2020 in underground forums. A one-time payment of .2 BTC (~ USD 1,900 at that time) licensed the ransomware, and an additional 20% of any ransom payment was billed through the platform. Smaug is an example of cybercriminals leveraging ransomware as a service (RaaS).

Targeted ransomware attacks spiked in the last 12 months and we can see some of the well-known groups using GoLang payloads in their recent operations. With global remote working and organizations facing challenges to keep their infrastructures secure, attackers will continue to become increasingly sophisticated, combining targeted and opportunistic attacks.

Some hacker groups known to use GoLang based malware extensively are SNAKE (also known under EKANS), Robinhood, Netfilim and REVil.

Two other good examples of malware built on GoLang are WellMess and QNAPCrypt.

WellMess malware can operate on Windows via PE and Linux via ELF (Executable and Linkable Format). Both versions are capable of the same functionality. The PE version can, however, execute Powershell commands. WellMess is a malware written in both Golang and .NET and has been in use since 2018. It is a lightweight malware designed to execute arbitrary shell commands, upload and download files. The malware supports HTTP, TLS and DNS communications methods.

FullofDeep, a Russian cybercrime group that also operates from Ukraine, focuses on ransomware campaigns. This cybercriminal group is known to develop ransomware payloads for the Windows and Linux platforms. They often targeted Linux -based file storage systems (NAS servers) and are responsible for QNAPCrypt ransomware.

Interestingly, the threat actors utilize geolocation information and skip infecting machines if they are in Belarus(BY), Russia(RU), and Ukraine(UA).

Non-PE Malware Threats

Non-PE threats, as the name suggests, are not Windows executables but other means of infecting machines. In this category, we include Office files, scripts, PDFs, and other non-windows-native formats.

There are other types of Non-PE threats such as PHP and Perl based scripts. However, they are rare and we report them as part of the’Other’ group. Part of the last 2% is Java binaries, most commonly known as the “.jar” filetype. Finally, exploits are specifically crafted files that trigger a known vulnerability in an application.

Commonly exploited software includes the operating systems themselves and other Microsoft products such as Office, Adobe products such as Adobe Flash (now end-of-life), and Adobe Reader. Cyber-attackers place malware in corrupted .doc files or an XML plain text file with trailing program code. Consequently, we include some PE files in this category.

One advantage of Non-PE malware is that it is mostly platform-independent. Once it has successfully infiltrated a system, the malicious script or document can choose what malware payload to use as the second stage, depending on the type of device infected.

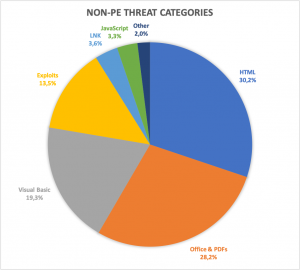

In the chart above, we can see how Non-PE threats vary. The majority of attacks are HTML and Office file-based. The Visual Basic category targets mostly Office files and only the ones containing VBA macro code.

Contrary to what we see with PE malware, Non-PE threats are prevalent in English-speaking countries. Most Non-PE attacks per device occur in Canada, Singapore, and the UK. However, Germany, Switzerland, Sweden, China and Australia are common targets. Ironically, some countries that were very likely to get attacked by PE malware have a far lower Non-PE threat level. South Korea is an example of this.

The differences here are extreme. France and Italy see a high NonPE threat. Here, the average user is exposed to 7-8 times more threats than Romania or Poland at a medium-low NonPE threat. A German user is four times, a British or Canadian user eight times more likely to get attacked than a French user.

The most prevalent Non-PE threats we have seen this year were for Office documents. Emotet spread in documents via macro VBA code, Excel documents containing Excel 4.0 macros, and encrypted documents.

Documents spreading Emotet

At the start of the year, documents containing Emotet were absent. However, by the beginning of the summer, and then into early Q4, we saw a surge in documents spreading Emotet. During the entire year, our generic detections have covered more than 30k unique Emotet loader samples.

Encrypted documents

Starting in early Q2, we saw a big increase in Excel macros as an attack vector. As the number of documents containing Excel 4.0 macros increased, attackers started to add encrypted documents to the portfolio of Office exploits.

The increase accelerated through the summer, reaching a peak in October, followed by a decrease in the last two months of Q4. These documents typically spread several malware families, including Dridex, Zloader, Qakbot, and Ursnif.

Web Threats

In our threat map above, we can see countries in the northern hemisphere are more likely to come across malicious web pages than those in the southern hemisphere. However, India appears in the most targeted countries again, alongside Singapore, Denmark and the United States (very high probability of web attacks). Next, come the Nordic countries, the British Isles and Belgium.

Near the top of the ranking, but following Belgium, we find Central Europe with the DACH region, France, Italy and Spain (all at high threat level).

The lowest level of blocked URLs was in North Africa and the West Asia region (medium to low threat level).

Android Malware Threats

In 2020, we saw a 35% increase in the detection of banking malware on Android. However, the rate of Android attacks declined over the year, suggesting that attackers and PUA developers shifted their focus from the Android platform to target Windows and OSX platforms.

Shown in the chart above is the mix of Android threat categories. The majority of attacks can be attributed to malware, adware, PUA, or riskware, but malware makes up the vast majority of registered threat responses on Android mobile devices.

On our global heatmap, we notice a different pattern than with other platforms. Iran, Algeria, India, or Pakistan see a very high Android threat level. Users in Japan, Canada, and Finland are at a medium Android threat level and see fewer attacks. Despite these variations, the range between the highest and lowest threats is relatively small, which means only a few countries have a significantly higher or lower threat level than average.

Here are the top malware threats on Android in 2020

Applications related to COVID-19

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, malware creators devised all kinds of tactics to exploit users’ interests and fears. This was demonstrated by the variant of the Cerberus banking trojan Corona-Apps.apk found on Android devices. It uses phishing techniques and the virus’s name to trick users into installing it on their smartphones.

The website is used as the infection vector for malicious applications.

The website is used as the infection vector for malicious applications.

We already did a detailed analysis of Cerberus back at the beginning of the year.

Stalkerwares

Applications detected as stalkerwares (spy applications also known as spouseware ) fall under the spyware category and compromise user privacy and local system security. The application can be installed without knowing the device’s owner or without their consent to spy on them. It then secretly monitors their personal information: photos, videos, messages, location data.

Faced with the increased activity of stalkerware applications on Android. Avira has joined the Coalition against Stalkerware to combat this threat.

AllTracker Family – the command & control center which shows information about tracked devices

Android banking Trojans

Banking trojans have always been very active among Android malware and 2020 was no exception. Apart from the tactic of using COVID-19 as a pretext, banking threats have also followed their classic approach: masquerading as a commonly used app, requesting unusual permissions, and attempting to steal bank card data.

An example of such tactics can be seen in a variant of the Android banking trojan family Wroba, which disguises itself as Google Chrome and uses overlay techniques to capture card credentials from certain monitored banking applications. In most cases, the overlay used is a clone of the monitored banking application’s login screen.

macOS Malware Threats

It is often thought that the macOS operating system is immune to malware. There may have been a time when this was the case, but not today. The adoption rate of macOS means malware writers actively target it and have developed ways to break into macOS systems.

Adware and potentially unwanted applications (PUAs) account for more than half of macOS detections this year. Script or Office-based attacks are prevalent on macOS and together account for 21.5% of attacks.

Some malicious applications, distributed through install packs, spam, or bogus Adobe Flash Player updates, exhibit several potentially unwanted behaviors such as intrusive ads or changing the user’s default search engine (which may pose a problem for user privacy).

Scripts or Office-based attacks are usually first-phase infections, which means that they download the payload after it successfully infiltrates the system.

macOS malware writers and adware distributors focus on the main markets for Apple devices. Consequently, the United States is the most targeted (very high threat on OSX), followed by Canada, Western Europe, Australia and Japan (high to a very high threat on macOS).

A few countries are in the “middle ground”, such as Italy and China. Although the number of attacks per device is high, they are significantly lower than in North America or Western Europe. With a few exceptions, Latin America, Africa and Asia see low rates of macOS-based attacks.

EvilQuest

This year, the macOS environment has seen a special kind of ransomware, named “EvilQuest”. This malicious program uses torrent websites as its infection vector, disguising itself as certain legitimate applications (Google Chrome or Mixed in Key 8 as examples). After installing itself on the victim’s computer, the malware makes itself persistent via a launch agent (meaning that the malicious program will start automatically).

In terms of ransomware capabilities, EvilQuest targets all sorts of files: from office documents (doc, xlsx) to PDFs and files related to keys, certificates and wallets (using regular expressions such as *id_rsa*/I, *wallet*.pdf/i).

What really makes this malware family special is its viral capabilities. Once the initial malware binary makes itself persistent, it will list the/Users directory’s content and infect every binary which is not part of an application bundle.

The infection mechanism works as follows: the original malware content is written to the start of the target file, then the target file is appended to it. After this, it writes a trailer to the end of the file, containing a specific string (DEADFACE) and the offset in the infected file where the original target is located (this offset is used to run the original file needed after the malware has been activated).

Adware & PUA

Adware and PUA are closely related to each other and, combined, they make up more than 50% of the total number of detections for macOS in 2020.

Some malicious applications exhibit multiple potentially unwanted behaviors such as intrusive advertisement and changing the user’s default search engine (which can cause privacy issues for the user). These include Tapufind, distributed via installation bundles, spam, or fake Adobe Flash Player updaters.

Another example of adware that is particularly aggressive is SurfBuyer. This adware doesn’t have to deploy itself on the user’s machine. In most cases, it’s included in other (legitimate or not) software that the user installs willingly. This behavior matches Avira’s definition of Potentially Unwanted Application, strengthening the fine line between PUA and Adware.

An example of advertisements that appear after the installation of Surfbuyer

An example of advertisements that appear after the installation of Surfbuyer

Installing Surfbuyer on the user’s machine enables it to display different kinds of advertisements and “coupons” and, in some cases, even download and install other PUA applications. Some users fall for these tricks thinking that the promotions are real (they sometimes are, but clicking them is still ill-advised).

IoT Malware Threats

Threats to ‘Internet of Things’ devices continued to increase in 2020. People spend increasing amounts of time at home and are investing in smart devices permanently connected to the internet. Granted, many of these devices are relatively secure, but a large minority remain vulnerable as a result of security flaws in the hardware or software configuration.

Since they generally do not require the regular intervention of users, threats that target connected objects focus their efforts on two infection vectors:

- The exploitation of remote code execution vulnerabilities

- Brute force credentials hacking.

The second technique relies on default passwords that have never been changed or are not sufficiently complex and remains a significant issue for IoT devices.

Threats that are more difficult to avoid are those that exploit known vulnerabilities on devices. IoT devices, particularly older ones, are likely to have unpatched security vulnerabilities that cybercriminals can use to gain unauthorized access to a home or office network.

Instead of categories, we have focused our analysis on family names for IoT. In the last few months, Sora samples were the most observed most by our IoT lab. Sora is one of the most notorious variants of Mirai malware, known for its high volume of samples found in the wild. It targets embedded systems, usually through exploiting device vulnerabilities.

One example of a device exploited by Sora is the Rasilient PixelStor5000 video surveillance storage system. Sora breaches by exploiting its vulnerability CVE-2020-6756.

This vulnerability allows an attacker to perform a Remote Code Execution. Mirai itself is one of the mainstays of the IoT threat landscape. Thanks to its publicly available source-code, Avira’s IoT Labs are continually discovering new variants. We have previously reported on Mirai and its evolution.

Owari is also a Mirai variant that made waves in 2018 when it managed to compromise nearly 20.000 IoT devices delivered via GPON vulnerability CVE-2018-10561. After successful exploitation, it then downloads its payload from the remote server. The authors of Sora and Owari are thought to be the same and dubbed “WICKED”.

Meerkat is a botnet that runs as a single instance by binding port 13324. It is often known as Lazy Meerkat. The botnet tries to manipulate the watchdog and prevents the device from restarting to establish persistence.

Other common IoT threats not shown here, and part of the “Other” group are Gafgyt and Katana. Latest Gafgyt samples exploit the Pulse Secure Connect vulnerability CVE-2020-8218. Gafgyt has exploited LG SuperSignEZ CMS, CCTV/DVR & ThinkPHP, and targeted GPON and Huawei routers through a command injection vulnerability.

Like many other IoT malware, Gafgyt also manipulates the watchdog and prevents the device from restarting.

Katana is a relatively new Mirai variant. Although the Katana botnet is still in development, it already has modules such as layer 7 DDoS, different encryption keys for each source, fast self-replication, and secure C&C.

Katana has its own Youtube Channel called VEGASec, where it can be bought and sold. The Katana botnet attempts to exploit old vulnerabilities via Remote Code Execution/Command Injection vulnerabilities present in LinkSys and GPON home routers.

Learn more about new and novel malware, or automatically receive our next malware threat report by subscribing to Avira Insights blog’s research section.

Visit oem.avira.com to determine how you can improve your detection rates using Avira’s anti-malware SDKs or threat intelligence.

Learn how to build your own security solutions with our anti-malware SDKs and threat intelligence.

Want to comment on this post?

We encourage you to share your thoughts on your favorite social platform.